Forgetting, remembering and dragonflies (Covid series: 2 of 15)

Want to learn something – a list of words, for example? Then don't sit there reading and re-reading. Instead, test yourself.

That's the simple message revealed by numerous studies over the past hundred years or so. Repeating an input is less useful than retrieving it from your mind. It may follow that learning programmes should therefore feature more testing.

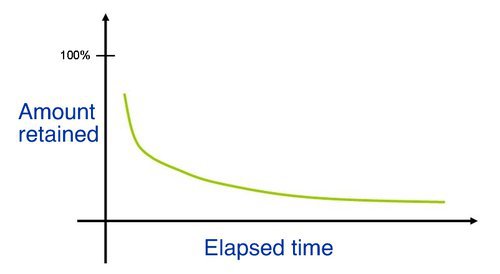

Everybody knows that things you've learned drift out of your mind as time passes. If you learn that the French for dragonfly is libellule, you'll probably be able to say the word when a dragonfly flits past five minutes later. But if another dragonfly appears the next day, and you've made no effort to retrieve the name in the interim, it can be very hard to recall the word 'libellule'. Back in 1885, a German researcher called Ebbinghaus formalised our habit of forgetting in the form of a graph:

Is it true that making an effort to retrieve the word helps learning more than simply repeating the mantra "dragonfly libellule … dragonfly libellule … dragonfly libellule” There's a good deal of evidence that it is, and you can find a great summary of that evidence in a book called Make It Stick by Peter Brown.:

For example, Brown highlights a 1967 study showing that "research subjects who were presented with lists of thirty-six words learned as much from repeated testing after initial exposure to the words as they did from repeated studying." The idea that testing rather than repetition improved memorisation was reinforced by a later study in which students were told a story which included sixty concrete objects. "Those students who were tested immediately after exposure recalled 53 percent of the objects on this initial test but only 39 percent a week later. On the other hand, a group of students who learned the same material but were not tested at all until a week later recalled 28 percent. Thus, taking a single test boosted performance by 11 percent after a week."

Make It Stick cites other studies in which testing was used as an aid to memorisation, and the results do tend to show that it can work better than repetition.

The implications for learning mean that if you include plenty of opportunities to retrieve information in your courses, learners are more likely to remember over the long term. This requires quite a shift of emphasis from testing to prove how much you've learned, to testing for the purpose of helping learners retrieve information regularly. That in turn means treating testing as a "private" activity, rather than something that earns you points, certificates or prizes.

You may be saying to yourself that this is hardly a revolutionary finding. Good teachers constantly question their classes, asking students to summarise, repeat and retrieve. The basis of the Socratic method is asking questions. The only difference proposed here is the formal nature of testing.

This is of course true. There's nothing new under the sun. But it is useful to be aware that spaced retrieval can be designed to help learners retain what they've learned.

This post is an update of the original from Coracle posted on 21st August 2015.